WARD 86: An Epidemiologist in the AIDS Epidemic, continued.

Chapter 2: Strange Ways of the Oncologists. September 1981

(Chapter 1 is here)

1

Market Street, San Francisco’s main street, runs southwest from the business district downtown and meets Castro Street a couple of miles out. The hills around the intersection look back along Market Street and over the Bay to Oakland. This hilly neighborhood around Market and Castro streets is “The Castro”.

The Castro was saved from the great fire that followed the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. The wind shifted on the third day of the fire and the flames blew south into the Mission District. In a last-ditch effort to contain the fire the Navy and the National Guard dynamited a firebreak along Dolores Street, the border between the Mission and the Castro. After a seven-hour struggle the firebreak held and the Castro was saved -- and, to the south of it, Noe Valley, a cluster of run-down, pointy-headed Victorian houses on the hills above the Castro.

I moved into Noe Valley in 1974. I was a 1960s dropout and I had turned thirty and decided to get respectable. I bought a crumbling Victorian house with a five thousand dollar down payment I got from my father in England, and went back to graduate school at Berkeley

About the same time, gay men fleeing the collapse of the Haight-Ashbury hippie culture began to homestead in the Castro. There wasn’t much in the district but the Castro Theater, a gorgeous art deco movie palace designed by Timothy Pflueger in the 1920s, and Cliff’s hardware store a few doors down the block. In the 1970s, Cliff’s ran a children’s costume contest every Halloween on a flatbed truck outside the store, and when I moved into Noe Valley, Halloween in the Castro meant the children’s costume contest on the flatbed truck. For a while in the seventies there was coexistence: the kids in their costumes came on first and then the weird, brilliant gay Halloween, displaced from the old-time gay neighborhood on Polk Street at the edge of the Tenderloin, started up afterwards. The first gay bar, Toad Hall, opened up opposite Cliffs Hardware at about the same time, with a clientele of gay hippies and a bubble machine over its front door. When I walked home down Castro Street in the 1970s, the bubbles would blow across the street from Toad Hall and drift lazily under the art deco marquee of the Castro Theater. By 1981 all the bars were gay.

By 1981 I have managed to finish my Ph.D and I have slid into a job at UCSF, the giant medical school up on Mount Parnassus. My children are riding the Southern Pacific commute train up from Palo Alto, where their mother is getting her Ph.D. I get up at six on Monday mornings to put the kids on the Southern Pacific and hope they don’t fall asleep and finish up in San Jose. Meanwhile I’m commuting to LA every couple of weeks to visit my blonde girlfriend Tora. Life is crazy.

My house is three blocks up the hill from the heart of the Castro, up past the Sausage Factory, where my sons play Pacman and Space Invaders on the machines, then up past the camera store where Harvey Milk held court, directing the political life of the district, until an ex-cop named Dan White assassinated him in 1978, along with Mayor George Moscone.

(“You used to talk to Harvey,” said an old girlfriend. But mostly I took my film into the camera store for development. I remember Harvey sprawled in his barber’s chair, not much interested in film processing, and his lover Scott Smith off to the side.)

Up Castro Street a little beyond the photo store and to the left is Liberty Street, a short block of cute Victorian houses, still ungentrified in 1981 but with a spectacular view down into the Castro and north over the city. This was my block

I was a cancer epidemiologist: that was what it said on my Ph.D. Environmental cancer had become the fear of the moment, so I went into that. I had big plans to attack the environmental crisis but I was marginal at UCSF. I was a graduate-school dropout of the crazy year, 1968. Six years later I had clawed my way back into a late Ph.D at Berkeley and then been fired from my first job at the Peninsula Cancer Research Institute[1] by a haughty Stanford lymphoma expert who was the Institute's Board chair. “He doesn’t like you because you’re a maverick,” my immediate boss explained, waving a hand at my rumpled corduroys and leather jacket. “You dress like that….”

Or maybe the Board chair didn’t like me prying into the lymphoma data. Stanford was the world’s leading lymphoma treatment center and I had come up with the idea of comparing their results with everybody else’s to see how good they actually were -- a dangerous idea on the face of it. Of course they didn’t want a scruffy, newly minted epidemiologist poking into the hallowed lymphoma studies. Either way it was a fundamental lesson in medical school life: don’t piss off the Chief.

But then I got a grant funded in environmental cancer, to study hormone exposure in men with testicular cancer, so I was marketable. Nick Petrakis, the chairman of the Department of Epidemiology at UCSF, thought it was unfair that they were booting me out of the Institute (for not being an MD, they said, though I wasn’t any less an MD than I had been when they hired me), and he took me into UCSF. He found space for my tiny research group in the old Public Health Hospital near the Golden Gate bridge. "Your group," as they say at UCSF, conjuring up the vision of a vast research empire. It was me and my secretary and Dennis Osmond, another graduate school dropout who had wandered into the cancer business. The smart, slightly goofy, six-feet-five Dennis Osmond, literary like me and a genuinely nice guy.

(Why am I so ambivalent when I write that Dennis was a genuinely nice guy? Because I don’t see how you can survive in this business as a genuinely nice guy, I suppose. But he did survive.)

In 1981 the Public Health Hospital was dying. Ronald Reagan was cutting budgets and public health was expendable. But I got another grant funded, this one on petrochemical exposure and brain tumors, and we were able to move up to ground level and into rented office space in a UCSF building on Gough Street, near San Francisco’s City Hall. It was one-year funding only, from money left over at the end of the fiscal year, but it was timely because some Marine dentists were advancing on our part of the basement. It was another lesson in medical school life, probably the most important lesson: get your grant funded!

There was a whole floor full of brain tumors at the UCSF hospital on Parnassus, a floor of stunned-looking people in knit caps, with, underneath the knit caps, radiation guidelines magic-markered onto their shaved skulls. Their life expectancy was a year or so. It was exotic and I liked the salty nurses and their gallows humor, but the Chief of Neurosurgery – Charlie Wilson, the world’s leading expert on pituitary adenomas -- floated through the corridors like an angry ghost and the neurosurgery Fellows flinched every time he came by. I had to duke it out with the Fellows -- doctors in the last stage of training, hungry for turf. They didn’t understand what a Ph.D in epidemiology was doing in a clinical department and neither did I: I was making it up as I went along. But brain tumors were scary and I had developed medical students’ syndrome. I was driving my decrepit 1964 VW bug to Berkeley one day when I smelled burning, a well-known symptom of brain tumors. I pulled over to the emergency lane in a panic and started to lecture myself: you’re imagining this, your brain isn’t burning. But no, I wasn’t imagining it: the Volkswagen was on fire.

At the new office on Gough Street we were subtenants to the Mellon Program in Clinical Epidemiology, a well-financed bunch of young UCSF doctors being trained to do research. At the end of the day at Gough Street I would take the streetcar home along Market, get off at the busy intersection at Market and Castro and walk south down Castro Street into the strange, ingrown, intensely political gay and lesbian village that had developed around Castro and 18th streets. This was the center of the universe for gay men. That day in 1981 I saw the front cover of the magazine Christopher Street on the newsstand and was struck by a jolt that felt the way an old Grateful Dead logo looks: a zigzag flash into the base of the skull. The story said there was a transmissible cancer of gay men running around the Castro. I bought the magazine – cautiously because, like all straight men living in the neighborhood, I thought I had to make it clear to the world that I was heterosexual. Buying Christopher Street off the newsstand was pretty suspicious (“you bought a gay magazine for research?”) but I bought it, because there was no such thing as a transmissible cancer and I was a cancer epidemiologist and the Castro was my neighborhood.

The article was based on the first two reports of what would turn out to be AIDS. These had been published in the June and July issues of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the MMWR. (The MMWR is a stodgy professional weekly the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta puts out for State and local health departments.) The first article said five gay men in Los Angeles had been diagnosed with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, PCP, a disease previously reported mostly in severely malnourished children. The second said 26 gay men in New York and San Francisco had been diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma, a very rare cancer producing red and purple skin lesions on the arms and legs[2]. Both groups of gay men had severely damaged immune systems.

In San Francisco, some of those Kaposi’s sarcoma cases had been reported by Marcus Conant, a dermatologist who had a clinical appointment at UCSF. Clinical faculty were private-practice docs who taught at UCSF but weren’t part of the university machinery, therefore inferior from the point of view of the tenured, hard-money faculty. But this last category didn’t include me. I had a soft-money adjunct appointment, meaning I had to bring in research grants to survive. I was a little higher up the ladder than the clinical faculty, but then I wasn’t a real doctor. I was very conscious of my status as a brand new but over-age assistant professor with no publications, and as a Ph.D in the land of the MDs. Whatever they tell you, it’s only the doctors who count in a medical school, unless you happen to be a world-class molecular biologist.

Luckily for me Marcus Conant was an outsider too. He was gay, which was perhaps why he spotted some of the first cases. But there were no out gay faculty at UCSF in 1981. UCSF was the mother ship of California medicine, the first medical school on the West Coast. In spite of its location in the far-out little city of San Francisco, UCSF was quite conservative in 1981 and open homosexuality was a no-no.

As for me, even though it made me nervous to buy Christopher Street, I was (I thought) relatively gay-friendly. I had been around the beginnings of gay liberation in San Francisco in the seventies, during a short career as a would-be writer, and I had edited a book called The Gay Liberation Book for Ramparts Press. The writers, two locals named Len Richmond and Gary Noguera, were attentive in a way that was much more attractive than the work-shirt-and-blue-jeans machismo of the student-radical universe I had come out of. I liked them. I enjoyed working with them. It turned out also that gay men liked working with straight men: the mild flirtiness kept things lubricated.

In 1981 I was still really a writer in my head. I had dropped out of graduate school at Stanford to be a writer and I only went back to graduate school in a post-Watergate, death-of-the-sixties moment of desperation in 1974 because I was trying to hang on to my kids. I was thirty and I thought I needed to be respectable. Four years later I came out of the Ph.D program at Berkeley thinking I was going to work part time and write, and I didn’t mind it when they pushed me out of that first job at the Pacific Cancer Research Institute and I landed at UCSF. I’ll write about them, I thought. I’ll write about the strange ways of the oncologists.

2

Actually I had enjoyed Dr X, my boss, the sweaty, overweight entrepreneur of the Pacific Cancer Research Institute, and his awkward relationship with Dr Y, the famous oncologist who was his Board chair. Dr X hated Dr Y because Dr Y was a snooty, aristocratic lymphoma expert with long, delicate fingers who could find swellings in lymph nodes that other people didn’t know existed. But Dr Y despised Dr X as a hustling carpetbagger from the National Cancer Institute who didn’t even see patients. So Dr Y never came into his board-chairman’s office at PCRI, and Dr X kept the office empty as a permanent reproach to Dr Y, and Dr Y wouldn’t give Dr X a real appointment at his medical school. “He won’t invite me to the conferences,” Dr X said plaintively. “He doesn’t think I’m a real doctor.”

In revenge, Dr X spread gossip about how Dr Y would always be in the shadow of Henry Kaplan, his mentor, who had invented Total Nodal Irradiation, the therapy that actually cured Hodgkin's Disease, which was the very first curable cancer, and how Dr Y was eaten up by jealousy and disappointment at the comparative failure of his own career. Henry Kaplan was still there, the grand old man at the medical school, looking like a small-town druggist in his suit and bow tie. He had two huge, swollen, misshapen fingers on his right hand, and when you met him he shoved his hand into yours and let you feel the fingers and deal with your reactions: I invented Total Nodal Irradiation: deal with my hand. I enjoyed the three of them. I thought the whole thing would make a great story.

Then the Assistant Director of PCRI got breast cancer and they fired her. I complained and Dr X told me she couldn’t do her job any more. “Well, I would say she couldn’t handle it,” he said, leaning towards me and staring frankly into my eyes.

I told him I didn’t agree with the firing. A couple of months later they fired me too. It might have been Dr Y who wanted me out, I wouldn’t be surprised, but at the time I thought Dr X’s oncological defenses had been compromised. The Assistant Director’s breast cancer was too close and he had gotten a twinge of fear. It made me think about the oncologists’ defenses, which would be an important issue for me in the near future. And then I was saved by Nick Petrakis, the chairman of Epidemiology at UCSF, an old-time scientist with an actual sense of justice, who thought I had been screwed, and I went into UCSF on a part time appointment with plenty of time to write. They did screw me at the Institute, but it got me into UCSF.

Thinking I was going to write about it all was, I suppose, my version of the oncologist’s defenses. And, like a vampire, Dr Y would soon reappear in my life.

3

I was actually writing about the Holocaust. It was a late-life discovery; my father’s family, back in England, were Jewish but I had never particularly identified as a Jew. Then in London in the summer of 1981, just after those first announcements of AIDS came out in the MMWR, I went to a National Front rally in Fulham. The National Front were actual fascists. I stood next to a very calm professional boxer, in the middle of a surprisingly large crowd of working-class Fulhamites, and I felt personally vulnerable for the first time in my life. When I came back I started finding swastikas on the walls of San Francisco – little graffiti swastikas drawn on the walls in all parts of the city. Nobody believed it but those swastikas were there. This turned my attention to the Holocaust.

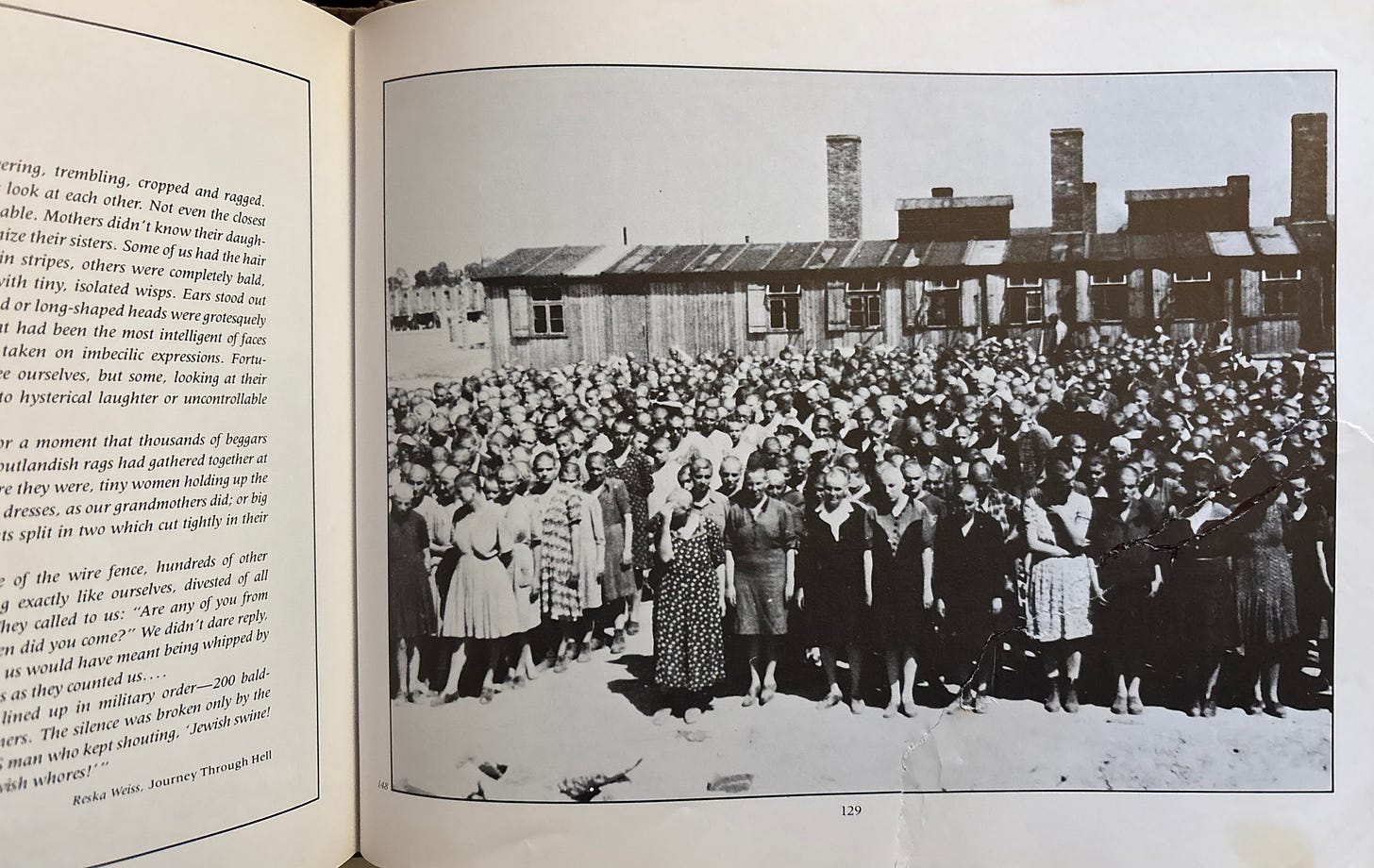

Early in 1982 I set to work on a review of the newly reprinted "Holocaust Album" for the San Francisco Review of Books. The album contained the only known set of photographs taken inside Auschwitz. It showed the selection process for new arrivals on the railroad siding, and then the long columns of women and children and old people marching off to the crematorium, and then the survivors who had gone the other way standing at attention in the mismatched clothing they had been handed out by the SS. An SS photographer had taken the photos and mounted them in an album, and then, after Auschwitz was closed down in the face of the Russian advance and the survivors were marched off westwards, the album had been miraculously discovered by one of the actual survivors, one of the women in the mismatched clothing. I thought it was a staggering document, like a holy relic.

Then I discovered that there was an original edition of the album out at the Holocaust Memorial Library on 14th Avenue, near my old office in the Public Health Hospital. I didn’t even know we had a Holocaust Memorial Library. I went out there. I found more holy relics: small bones, bars of soap, eyeglasses.

Attached to the library was a group of survivors who were available to talk to high school kids as part of the State curriculum unit on the Holocaust. I couldn’t believe this: these were the actual people who had got off the trains at Auschwitz, who had been sent right at the Selection and had stood at attention on the parade ground while the old and the weak and the women with children were sent left and up the chimney. I took notes. I burrowed in. I talked Max Garcia, a Dutch-born Auschwitz survivor, into letting me follow him to the local high schools, where he would answer the questions of bemused 12th grade students taking the compulsory Holocaust unit.

“At the roll call we stood for hours,” he told them.

“What did you do about going to the bathroom?” a kid asked.

“We went in our pants!”

“Pee-ew” the kid said.

I became a Holocaust researcher. I hung out with Marta Kohn, the distracted library director, wife of a survivor, who was apologetic because she was only half-Jewish (like me!). I started interviewing the survivors -- “Show him the tattoo, Max,” said Max’s wife. I wrote about it all for the San Francisco Review of Books. I was happy. This is what I was doing to get away from brain tumors, you figure it out.

I have to admit there is something in me that likes creepy subjects. I was smoking a lot of dope then, and I had learned to light up and let myself sink through the layers of paranoia, finding out what it was that I was afraid of. More exactly, finding out the order of the things I was afraid of by the order in which they came up. It was a way of testing my defenses – important for those of us in the cancer business. With cannabis you could let yourself sink in and feel the approach of one fear after another – the Jewish fear that all the conventions of society could collapse and you could be rounded up and marched off to the camps; the fear of brain tumors; the career fear of a thirty-seven year old assistant professor with no publications; fear that my children had been exposed to whatever the weird disease was that was running round the Castro….

…the weird disease that was running around the Castro! My oldest son Diccon[3] came back from the Sausage Factory at Castro and 18th, where he played Pacman with his friend Marvin, with a brown mark on his upper arm. It was the first time the disease got past my defenses. Yes, it was fear of AIDS (not yet called AIDS), low on the list but definitely there. It came back to me that night in a nightmare in which I was watching Stanley Kubrick’s movie The Shining -- Diccon’s brown-marked arm merging with the rotting corpse of the woman in the bathtub.

“I am holding back on Diccon’s Kaposi’s sarcoma,” I wrote in my diary. “Spreading blue-brown marks.” I had read the MMWR reports the previous July but they didn’t get my attention; Diccon’s brown marks produced actual fear. It was the real thing -- visceral, a shudder.

This was the beginning of 1982 and my subconscious, at least, began to pay attention. I opened my ears. I clipped the press. I learned from Newsweek that it was really an epidemic of immunodeficiency. I started picking up the gay weeklies, the Bay Area Reporter, the Voice and the Sentinel. I was trying to understand gayworld, trying to bridge the gap between myself and whatever was happening down the hill in the Castro. Up on Liberty Street we were next to that universe but not in it. The only straight person on my block who had entrée to gayworld was Medora Paine, the teenage daughter of my very politically correct neighbor Gretchen. Medora was famous; she had gone down the hill to Harvey Milk’s photo store, talked her way into his first campaign and become part of his political machine. Early in 1982 I began to pay attention. Auschwitz was the focus of my life but my subconscious had discovered AIDS

[1] Not its real name.

[2] At the time KS was so rare in the US that only about two thousand cases had ever been reported, most of them in people who had had their immune systems suppressed for kidney transplants.

[3]. Yes, it’s a sixties name. So far as I know he’s the only Diccon in the United States. He changed his name to William shortly after this.

thanks, Andrew--hope you find a publisher, but happy to read the next installment

I was startled to notice a slight connection to the brain tumor part of your story. My neurosurgeon, Dr Brian Andrews, has written a biography of Dr Charles Wilson. Trying to get to know him, I read the book with its many scary (to me) descriptions of brain surgery techniques.