Ward 86: An Epidemiologist in the AIDS Epidemic -- Chapter 5

Research. September 1982

(This is the fifth chapter of my memoir of working in the early days of the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco. It starts in the fall of 1982 when I joined the research group at UCSF, and then when I came face to face with a man who was dying of AIDS. Chapter 4 is here and the first chapter is here. )

1

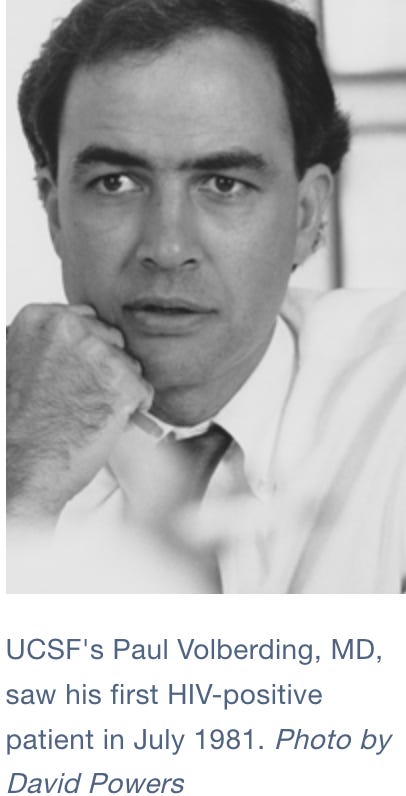

At home in San Francisco Paul Volberding’s photograph was in the San Francisco Chronicle. Volberding was the young oncologist just out of his fellowship who was treating the Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. He was starting a high-dose interferon trial for KS, the story said, but the trial was going to be at San Francisco General Hospital, the county hospital down in the Mission District, not at the University hospital on Parnassus. For some reason the patients were being referred to General. And from what I was hearing interferon was a long shot, something to throw at the KS patients because standard chemotherapy didn’t do much for the immunodeficiency that was the real disease.

I forced myself to walk down the hill into the Castro. In Gramophone, the bookstore at Castro and 18th, I bought Time magazine (“Herpes: 20 million cases” it said on the cover) and I picked up the gay papers. A flyer on the wall advertised an album called “Music for Sick Queers.”

Music for sick queers?

I strolled round the corner to Letitia’s, a bar on Market Street, to read the gay papers and ran into a systems analyst from the Mellon Program in Clinical Epidemiology, our landlord at Gough St. “I'm following that Kaposi’s sarcoma stuff in the gay press,” I told him, feeling, again, that I had to defend myself against the imputation of queerness.

“You can get that in the straight press,” he said.

I failed to come up with a snappy response.

Back on Castro Street, I recognized Scott, Tora’s former downstairs neighbor from Venice, standing outside the deli. He was munching on a succulent-looking baguette sandwich that was dripping melted cheese.

“Are you still working on that Kaposi’s sarcoma stuff,” he asked, lowering the baguette. “Because I had another friend that died of it. He’s been disappearing for a year.”

People were disappearing all over the Castro, he said. One man in his AA group. The guy that ran the old furniture store…

I asked for a bite of Scott’s sandwich -- it was irresistible -- thinking, even as I bit into the baguette, that the reason you wipe the bottle’s neck before you drink is fear of infection. The thought was too late: I went ahead and chewed my mouthful anyway.

Scott pointed down at his foot. “I even have red marks on my heel.”

I felt myself dissociating. My consciousness moved back up Castro Street, rose a few feet into the air, and looked down on Scott and me from above. I watched myself give him back his sandwich.

"Welcome back, Andrew," said Castro Street.

***

The powers that be at the National Institute for Environmental Health Studies had funded the brain tumor study for another year, so we were still in business. Scraping together money from small grants, plus five thousand dollars that my chairman Nick Petrakis had pried out of the Dean, I hired myself a gay associate. This was Michael Gorman, an anthropology PhD from the University of Chicago with an MPH in epidemiology. He showed up for the job interview in full-on butch mode -- looking fierce and brushy, with short hair, bristling moustache and almost-military aspect. But by the end of the interview he had relaxed into something like cuteness. This made me feel powerful, of course.

Michael was my gay protection, that was the idea. He was going to be my interpreter and guide to the mysteries of gay life. With Michael I went to a meeting of the Gay Caucus of the San Francisco Medical Society, to meet the doctors so I could recruit their patients for our studies. I found myself in a McDonald’s on Market Street, sitting with Michael and Bob Bolan, the president of BAPHR, the Bay Area Physicians for Human Rights, waiting for the caucus to begin.

BAPHR (pronounced Bafra) was the professional organization of lesbian and gay doctors. Marcus Conant, I knew, was not impressed with BAPHR and his nurse Helen Shietinger said sniffily that it was mainly a social group. (Marcus Conant had taken three years to come out to her, Helen told me. And why was she herself interested in all this, I asked. She bridled, went silent for a moment, then awkwardly announced that she was a lesbian.).

We sat in McDonald’s waiting for the Gay Caucus hospitality session to begin and Michael ate a hamburger. “You’re the only hyperthyroid,” Bolan said, laughing. A fat, middle-aged man and his beautiful blond son sitting at the next table eyed us occasionally. Eventually the father came over and said “you gentlemen look like you know your way around.” Somewhat startled, and wondering if this was some kind of sexual innuendo, I directed him to the freeway.

Bolan followed the blond boy with his eyes as he went out the door. “Not a chance, not a chance,” he said.

“You can sit on my face,” he said, as the blond boy disappeared. He put the menu up in front of his face and giggled. “You must excuse us lechers,” he said.”

“OK,” I said, feeling awkward. I looked at Michael Gorman to get some cue on how to respond to this. Michael, disapproving, was silent.

2

Marcus Conant’s Kaposi’s sarcoma clinic was the place to go to hear about the new disease. Conant ran an actual clinic for the Kaposi’s sarcoma patients on Thursday mornings, in the outpatient clinics building across Parnassus St from the UCSF hospital. But afterwards he ran a discussion session, officially the KS Study Group but also loosely called the KS Clinic, and this session was the meeting place for everybody interested in the thing.

Conant presented his Kaposi’s sarcoma patients at the KS Clinic. He also raised the social issues around KS with steely persistence, reminding everybody that this disease was different because it was a deadly outbreak in gay men, and gay men were a vulnerable and highly stigmatized population. Same-sex sexual activity had only been legal in California since 1976 and was still a criminal offence in half the States.

The KS clinic was the meeting place for the group that Conant was pulling together to write the grant proposal for the NCI -- the group that he had invited me into -- but it was also open to anybody in the UCSF community who was interested. It was a clinic in an old-fashioned sense: a public theater where a patient was put on display for the education of interested parties.

Taking a cautious place in the back row I thought of the infamous hysteria clinic run by the Paris neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpetrière hospital in the 1880s. At Charcot’s clinic the female patients acted out Charcot’s version of hysteria for a society audience, twisting themselves into extreme “hysterical” postures as they had somehow subliminally been taught by Charcot and his assistants. Marc Conant’s patients didn’t act out their disease but they did display their lesions. The KS Clinic was the public theater of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

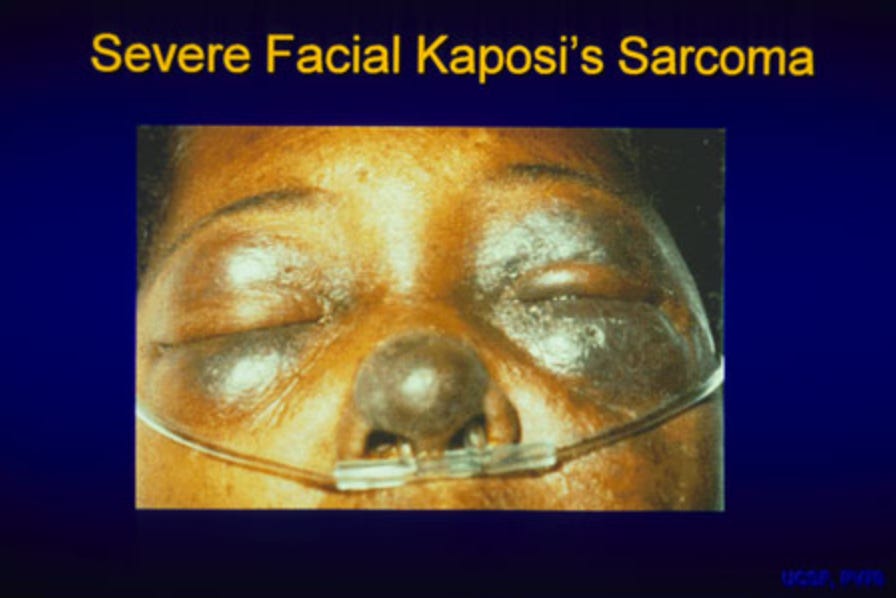

This Thursday the patient down in front was Mr Washington, an African American gay man who had both Kaposi’s sarcoma and syphilis. Conant told us the lesions of KS and syphilis looked similar on black skin and he pointed a few lesions out. “Come on down,” he said, beckoning us to move in for a closer look. Then, turning benevolently to the patient, “Show them a good one.”

“Ain’t no good lesions,” Mr Washington said sternly. He lifted a leg and pulled up his pants. Conant mumbled guiltily.

We went down and crowded in and ran our fingertips over the plump and darkly purple lesions on Mr Washington's arms and legs. On his chest was the three-inch scar of an incision lung biopsy. Following Conant’s instructions I felt the induration, the raised edges, of a KS lesion. I got excited feeling the edges under my fingers. It made me feel like an insider.

Mr Washington was a bartender at the Pendulum bar, just up 18th from Castro, which I knew was where you went if your taste ran to black hustlers. I passed my fingers over the edges of his lesion, felt professional, and went back to my seat, repressing the thought that something might have come off on my fingers. Donald Abrams, the Heme-Onc fellow, was at the back of the room too, jittering a little, anxious to be at the center of things himself. I had given him a version of the Kenny Paine speech and told him I lived in the Castro.

“Better watch out,” he said.

Conant moved to center stage and lobbed up a softball. “This disease has been named GRID by the CDC,” he said. “For ‘Gay Related Immune Disease.’ What do people here think of that?”

“What do you think of that?” I asked Abrams. He hadn’t told me he was gay -- nobody at UCSF was telling anybody that yet -- but from his body language, and from a verbal style that occasionally floated up into a high register, I thought he was. He cocked his head and gave me a look that was easy to read: how would I like a lethal and maybe highly contagious new disease to be called, say… Jews’ Disease?

Conant closed the conference. On the way out a tall, skinny psychologist named Paul Dague, who worked as a therapist with Conant’s KS patients, said hello. We went out to chat in the lobby of the outpatient building, looking out at the blue-green Golden Gate and the orange towers of the bridge.

Dague was nervous: something was wrong. I knew him as a touchy-feely shrink who believed in visualization and curing your own illness by the power of positive thinking. Now he fingered his ear. “I had a cyst on my ear which Marc Conant biopsied,” he said. “And it wasn’t a cyst. Now I have a chance to try out these methods in my own life.”

I suppressed my thoughts about visualization, smiled and nodded -- because I hadn’t quite caught on -- and we left. Out on Parnassus Street I thought What? Did I hear that right? Is he telling me he’s got KS? Did I decide not to hear it?

I had a quick moment wondering if I should not have shaken his hand

3

I still have the yellow sheet of legal paper with my hash marks on it from June 1982, the first time I sat down in Selma’s office and actually counted the cases. I think of that sheet of paper as a historical relic: someday it’s going to be in the Smithsonian.

I knew from the count on that yellow sheet that in June 1982, when Conant invited me into the UCSF research group, a total of 27 cases had been reported in San Francisco. Now in September there were about 50 cases. But this was probably an underestimate, because why would any gay man want to be known as an AIDS case? And then there were all the gay men with lymphadenopathy Donald Abrams was following – more of them than the cases. And then there were the mysterious early cases that floated up out of the medical records: Boettger, a gay paraplegic with KS at the VA hospital in early 1980, was he a case? What did it mean that he was paraplegic? He was in a wheelchair, was he having sex? I got hold of his address book, but none of the names in it were on the list.

The list. The list was the list of cases in Selma Dritz’s office, part of the bigger list the CDC was collecting of all the AIDS cases in the country There were 593 cases on the CDC list in September 1982, three quarters of them in gay men.

Darrow was working off this list for the CDC’s case-control study. “The CDC death list,” Stuart Anderson called it, as in “How do I get off the CDC death list?” I can see why a gay man might want to get off the list in September 1982, when nobody knows how far this thing is going to spread--or to whom. Is it safe to walk through the Castro? Is it safe if your dinner is served by a gay waiter? What about shaking hands with your gay friends?

Those things are safe, we the UCSF researchers are saying in the fall of 1982, crossing our fingers behind our backs. Because what if they aren’t safe? They probably are, we hope they are, but it’s too soon to tell.

“If they weren’t safe you’d have the thing showing up in heterosexuals,” we say, and so far there aren’t any heterosexuals on the San Francisco list. But what if there’s a long latency period, what if it takes years from when you get infected to when you get sick? What if the heterosexuals are just getting infected now? We don’t say this, or at least we only say it to each other. And it’s beginning to look as if there is a long latency period. There are not only a lot more gay men with lymphadenopathy than the reported cases, there are also a lot of men with reversed T-cell ratios. Thanks to the invention of the Fluorescent Automated Counter-Sorter, the FACS machine, the immunologists can now measure the different subpopulations of the white cells of the immune system in circulating blood.We are all learning about T cells now, the T4 and T8 lymphocyte subpopulations that are central to the immune defenses[1]. Normally there are about twice as many T8 cells as T4 cells in a person’s blood, i.e. a T8 to T4 ratio of 2. A reversed T-cell ratio – less than 1 -- means you have a shortage of T4 lymphocytes and that’s what the men with AIDS have. The really sick patients have no T4 cells at all.

In the Castro, gay men are coming into doctors’ offices asking to have their T-cells tested. Conant doesn’t want us to interview them about sexual behavior because he doesn’t want the T-cell count to become a scarlet letter -- you have a low T-cell count so you’re gay. It is still not all right to be gay in many circles, even in San Francisco. Not everybody wants to be out at work. We are still in the penumbra of Anita Bryant’s crusade against gay rights laws in Florida and then nationwide. "As a mother, I know that homosexuals cannot biologically reproduce children," Bryant said. “Therefore, they must recruit our children”. Bryant, a former Miss Oklahoma, was the author of a 1976 book called "The Survival of Our Nation's Families and the Threat of Militant Homosexuality.

In California Bryant’s activities had led to the Briggs initiative, a 1978 bill to prevent lesbians and gay men from teaching in public schools, the first attempt in the US to restrict gay rights through a statewide ballot.(Briggs was a State Senator from Orange County.) It failed after a major gay-organized campaign against it but Briggs and Anita Bryant were both still out there, organizing back. Now Bryant had made an alliance with a creepy fundamentalist organization called the Moral Majority, led by Jerry Falwell, that had originally been started to oppose abortion. Out there in Real America, far from the Coming Home diner, the fundamentalist right was mobilizing to make homosexuality a wedge issue.

And nobody knows what insurance companies will do about all this, I thought. Will they refuse to insure you if you’re gay? And what about employers? What about liability? How much damage is this thing going to do? These were the things Conant made us think about at the KS Clinic.

***

I knew there weren’t any heterosexuals on the San Francisco list because I was down in Selma’s office in the Department of Public Health office at 5 Grove Street, across the street from City Hall, organizing her data. Her data was clearly in need of help. Dennis and I sat in Selma’s office and organized it, using the diagnoses the CDC had just put together to make up its new definition of the “Acquired Immuno-deficiency syndrome.” They had defined the syndrome as a collection of ten different protozoal, fungal, bacterial and viral infections and two forms of cancer [2]. So now AIDS had been named and defined and the unfortunate label “GRID” was quietly disappeared.

John Ziegler, at the VA, is an expert on the lymphomas a few of the men are getting --“Burkitt’s-like” lymphomas they are called -- and he’s in the Lancet this month with an article reporting four of these lymphomas that have been seen in San Francisco so far. This is a major coup because publication in the Lancet, the leading British medical journal, is an enormous deal. Not coincidentally Ziegler is making a play for leadership in the research group at UCSF. Now Marc Conant calls me up and tells me “We have a bit of a problem with Ziegler.”

I feel loyal to Conant because he brought me into this but I can sense that he’s getting shunted aside. Everybody knows he’s the wrong kind of person to lead an NCI grant application, not a researcher, not quite one of us. Paul Volberding, the leading clinician in the group, is the likely principal investigator because he’s got the patients (and he's tall and beautifully dressed too).

But now, Conant tells me, John Ziegler wants to be principal investigator.

“Maybe you can have two principal investigators?” Conant says.

I know you can’t have two principal investigators; only one person can have budget control, which of course is the only thing that counts.

“Well,” Conant says, “we should vote for who we want.”

I tell him I vote for Paul Volberding. Volberding is a relative nobody like me and not threatening. “They only gave him that job at General because they wanted to keep his wife,” says the gossip at the KS Clinic. (Volberding’s wife is a hotshot internist in the General Internal Medicine department.) I’m pretty sure Ziegler will try to push me out; he already wants to cut the epidemiology budget and I get the feeling he thinks he can deal with epidemiology himself. So I tell Conant I vote for Volberding. He seems relieved.

Meanwhile a creepy rumor surfaces about Volberding: he’s been heard muttering that these diseases really are infectious. Keeping this thought about half repressed I went down to General to visit him.

4

San Francisco General, the county hospital, is deep in the Mission District, the heartland of San Francisco. Running along Potrero Avenue in the Mission is a string of six-story art deco brick buildings with vaguely Hittite ornamental plaques over the doors. These are the “old buildings” of San Francisco General, the buildings where I will eventually spend twenty years of my life. The old buildings were elegant once, but at some point some of them were given gigantic add-on outside fire escapes so now they look like huge invalids on crutches.

The main hospital is a brutalist concrete megabunker set back on a weedy green field between two of the old brick buildings. In the middle of the weedy field stands a gigantic rusted-steel sculpture on a concrete plinth. The sculpture looks like the flattened pelvis of a huge metal animal that has been dissected out and laid down gently on its side. The hospital’s patients have ignored the landscaping and worn tracks from the bus stop on Potrero Avenue around the sculpture and into the building[3].

Inside, in the buzzing entrance hall, high up and out of reach of vandals, hangs a famous Diego Rivera painting of a boulder-shaped woman who is making tortillas. The painting is a sign of the hospital’s mostly Spanish-speaking patient population, from the Mission District on the other side of Potrero Avenue. SF General is the poor people’s hospital, serving the city’s large heroin-addict population and the downtown homeless as well as the Hispanic immigrants of the Mission. For whatever reason -- discomfort with homosexuality or fear of infection -- this hospital rather than the university hospital up on Parnassus is where the powers that be at UCSF have decided to put the mostly white and mostly middle class (and so far all gay) AIDS patients.

There was a lot of art in the hospital, the fruit of Governor Jerry Brown’s California Art Commission. I had been taken on a hospital tour by one of the Mellon Fellows from Gough St. I caught a glimpse of a famous cardiologist making a ward round and was astonished to see him. The Mellon Fellow wasn’t. “This is a good hospital,” he said. “Probably the best in the city for anything but tertiary care. This is where they bring you when you drop.”

SF General was and is a city hospital but the doctors and researchers are UCSF faculty. The nurses are split and the hospital itself has a schizoid personality, half university, half City. In the City you don’t stick your neck out, the Mellon Fellow said. And Selma Dritz’s boss, the head of infectious diseases at the City, was somebody you needed to go around.

But Volberding had the right personality for the job, the Mellon Fellow said. “He’s smooth and he doesn’t make enemies. This job is going to be pretty good for his career.” As it turned out, this was a cosmic understatement,

Volberding’s office was on Ward 5A. Nice silk-screen prints hung on the walls, fruits of the Arts Commission. I waited in the tiny office, skimming back issues of Cancer, while Volberding and his nurse Gayling finished seeing a patient. He had posted a photo of his wife and kid on the wall, meaning he wasn’t gay.

Volberding came out of the patient room saying “quarter dose” to Gayling. He was younger than me, very tall, dark-haired, plump-faced and full-lipped like the young Marlon Brando and he was dressed in a beautiful, sober oncologist’s suit. The suit reminded me of Dr X who had (maybe) fired me at PCRI.

The patient was in the new high-dose interferon trial but he wasn’t able to tolerate the full dose. He was having a bad reaction, Volberding said, fever. He was anxious, thin-faced, tired. He had looked up at me through the doorway with a wary look that I knew from brain tumor patients: What fresh hell is this?

Volberding was seeing all the KS patients here at General, he told me. Nobody had been interested in the opportunistic infection cases till recently (Conant’s nurse, Helen Schietinger, said this was because the infectious disease people weren’t used to seeing all their patients die). But now, suddenly, everybody was getting interested. In the research group we had focused on Kaposi's sarcoma because that was what the NCI cared about, but from Selma’s data I knew that about half the patients presented with opportunistic infections, mostly Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (later renamed Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia). Volberding said if we wanted to interview the PCP patients I should talk to one of the chest people up on Parnassus.

Smiling, Volberding said he had talked Selma out of being the Principal Investigator for the epidemiology section of the proposal. This meant I was it. I left the ward feeling thoughtful, having passed some kind of test. As I left Volberding was making cheery but meaningless remarks to an incoming patient.

***

Back at Gough St Dennis had returned from a KS Clinic meeting. “Remember that psychologist?” he said. “The biopsy came out positive.”

Paul Dague, poor Paul Dague, I thought. Paul Dague has got it.

5

Dennis and I camped in Selma’s office in the DPH building by City Hall, cleaning up Selma’s data whether she liked it or not. We sorted the case reports and eliminated the ones with diagnoses that weren’t in the syndrome, like Hodgkin’s disease. This was very scientific and it made us feel good, but it undoubtedly pissed Selma off. We had simply invaded her turf.

I had sized Selma up as powerless and started pushing her around, on the grounds that I knew what I was doing here, we needed to figure out what was happening in the city, etc etc. She had a clear feeling of inferiority because she wasn’t academic, and she started furiously handing me publications with her name on them -- “Venereal Aspects of Gastroenterology;” “Foreign objects in the Rectum.” I riffled through them, filed them mentally under weird[4] and started marking the cases on a map.

The map. The map was an ordinary street map of San Francisco with color-coded marks on it for the cases – fifty cases now in September 1982. I made the marks black for the opportunistic infections, red for KS, and green for the (rare) lymphomas. The cases were down south of Market in the gay leather zone around Folsom Street, and then up along Polk Street, the old gay neighborhood next to the Tenderloin. There were a few cases along Market Street, and then many in the Castro, where the red circles clustered thickly at Castro and 18th . Then the cases came up Castro Street to my house and beyond into Noe Valley. I organized the cases by census tract, and my census tract, 206, had the highest number of cases in the city.

I shaded the census tracts by cases per head on a city map and made a picture of the San Francisco epidemic. “Nobody knows about this but me,” I thought. “I am drawing the boundaries of the ghetto”. I fantasized about barbed wire fences around the neighborhood. What about the real-estate values, I thought. What about tanks around the perimeter? This was all ripe material for Alterman, my paranoid fictional character, who soon began to stir.

Alterman was a character who had escaped from a novel I was writing (unsuccessfully) in Tora’s study down in Venice. He had got loose of the novel and made his way up north and was now an interviewer in an imaginary study called the Sex and Death Study, which was a lot like the case-control study Bill Darrow was doing for the CDC. Alterman emerged gradually in my diary over the fall of 1982, first watching the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, then noting the assassination of Bashir Gemayel the Lebanese prime minister on September 14. Alterman was still deep in Jewish paranoia, having not quite emerged from the basement of the Holocaust Library on 14th Avenue. Over the fall of 1982, however, he would leave his Jewish paranoia behind and embark on a different set of fears.

Meanwhile, we had to write the grant.

6

Writing grant proposals is a soul-deadening process that fills the average researcher with horror. I, personally, know that when I arrive at the gates of Hell, the reception devil (looking rather like Bruce Chabner of the NCI) will grin fiendishly and say “Welcome, Andrew. Your job for eternity is responding to Requests For Applications from the National Cancer Institute.”

“And believe me,” he will say, “none of your proposals will ever get funded.”

However, like the prospect of being hanged in the morning, writing grant proposals does wonderfully concentrate the mind. All of us in the group Conant had assembled began to focus on writing the proposal, and on sizing each other up as potential collaborators and research bedfellows.

In mid-September we met in the waiting room of Conant’s office in the Castro. Helen Shietinger, his long-suffering nurse, was just back from a lesbian and gay health meeting in Texas and had been scandalized by the callousness of the doctors. “They’re all talking Nobel prizes!” she said. Helen had political connections to Cleve Jones, a prominent gay activist and an inheritor of part of the Harvey Milk legacy, and to Pat Norman, the senior lesbian in the Department of Public Health. AIDS, like everything lesbian or gay in post-Harvey Milk San Francisco, was political. I was beginning to understand this.

I arrived with Art Amman, a short, square, sandy-haired pediatric immunologist with a friendly disposition who was one of the two immunologists in the research group. A receptionist came out, asked us who we were and told us Conant was busy and we should wait. Amman shrugged and we sat down.

Conant finally came out, Ziegler and Abrams and the laboratory scientists arrived and Volberding showed up last. This was clearly a formal situation. I was on the bottom, I realized, perhaps above Donald Abrams because he was only a Fellow, but then he actually treated patients. (This of course is what counts in a medical school.)

Ziegler, it turned out, had been voted out of the leadership. Conant, by tacit admission, was not the right kind of person to lead a big NCI grant –not a researcher -- so Volberding would indeed be the overall Principal Investigator. (Or was it that Conant was gay?) Thus it was appropriate that Volberding had turned up last at the meeting. Our vote would eventually make him a global star of AIDS.

The other immunologist in the group was the less eminent Dan Stites, who was nonetheless chair of Laboratory Medicine. Stites was doing the T-cell counts for those who had money to pay for them. He had a nice gay associate, Conrad Casavant (we don’t officially know he’s gay yet; people are still not coming out of the closet even in the research group). Conrad was another Ph.D; however, I was the only Ph.D on the proposal as a section principal investigator. There were two virologists, Jay Levy and Larry Drew. Drew worked with cytomegalovirus but not at the molecular level. “He’ s not a virologist” sniffed the Eminent Molecular Biologist when I asked for a reading. The EMB allowed reluctantly that Levy was a virologist. The word on Levy at the KS clinic was that he had run out of funding and needed a new project to keep his lab going.

Where was Marcus Conant on the proposal I asked Paul Volberding afterwards.

“I thought epidemiology,” he said innocently, giving me a frank and open smile.

He’s shoving Marc in with me, I thought. So I have to do Marc in. It was my first experience of Volberding’s management style.

But I voted for you, I thought.

Poor Marcus, I thought. But he isn’t a researcher!

7

Now I have to talk about epidemiology. This may be difficult.

Holding the image of the reception devil at bay, I proposed two studies in the grant proposal. The first was a case-control study of risk factors for AIDS in gay men. This was exactly what the CDC was doing but I didn’t quite admit that thought to myself at the time. Anyway, I told myself, theirs is a sloppy little study with controls out of the STD clinic, what a mistake. (Men in the sexually transmitted diseases clinic were at very high risk and many of them would eventually turn out to be HIV-infected like the cases. This meant the CDC study was very insensitive.)

Case-control studies work by looking backwards from the cases, exploring for previous exposure to possible risk factors. They compare the odds for exposure to the risk-factor in the cases to the odds for exposure in matched controls, giving a not-very-intuitive number called an odds ratio[5]. If an exposure has been equally likely in the cases and the controls, the odds ratio is 1. If the ratio is significantly bigger or significantly smaller than 1, by a statistical test, then you have “evidence of an association,” as we say. For example, the odds ratio for lung cancer in men who have ever smoked compared with nonsmokers is actually around 15 (and very significant). This kind of association is not regarded as proof of cause but as something about two degrees weaker -- because it depends on subjects remembering their exposures, among other sources of bias. Even so, the case-control study is a standard epidemiological method for exploring risk.

I also proposed a cohort study in which we would follow a group of gay men over time. The cohort would be made up of the two groups of controls in the case-control study plus the sexual partners of cases. These three groups of men, about 450 in all, were presumably at three different levels of risk for a sexually transmitted agent, with the sexual partners of cases being at highest risk. We would follow them to see who would get sick, and how fast, and what would predict sickness. (The idea of following a cohort of gay men to their deaths was another thing that had caused Alterman, my fictional character, to stir. He was probably thinking of the CDC’s Tuskegee Study, which had followed a cohort of African-American men with syphilis who did not receive treatment even when penicillin became available. The study became public in 1972 in a huge scandal that rocked the CDC.)

Cohort studies like this, also called prospective studies, compare the risk of disease over time in people exposed to a possible risk factor to the risk in those not exposed to the factor, giving a more intuitive number called a relative risk or risk ratio. This is more like the way we usually think. For example, in one classic study the relative risk of heart attack in men with serum cholesterol greater than 250 mg/dL versus those with less than 190 mg/dL was about 7. This means men with the high cholesterol measurement were about seven times as likely to get a heart attack over the course of the study as men with the low measurement.

Prospective studies are also used to study the natural history of a disease, for example to explore possible early predictors of illness in healthy people (e.g high blood pressure for coronary heart disease). Everybody was uneasily beginning to suspect that the T-cell ratio was an early predictor of AIDS in gay men -- uneasily because, as more gay men got the test done, a “reversed T-cell ratio” of less than 1 was beginning to seem unpleasantly common.

Prospective studies are thought to be the gold standard for identifying risk factors but they are much more expensive and time-consuming than case-control studies because you have to wait for the disease to happen. In our UCSF research group some occult process between the leading investigators had decided that each of the seven principal investigators collaborating in the proposal -- two virologists, two immunologists, two clinicians and me -- would have a budget of about a hundred thousand dollars a year; this wouldn’t get us very far with a prospective study. As a result I skimped on it in the proposal, which was a very bad mistake.

I skimped because I was ignorant about infectious diseases. This ignorance had become normal in epidemiology. By 1982 most epidemiologists outside the CDC had given up working with infections. The consensus was that in developed countries infectious diseases had been mostly wiped out by antibiotics, vaccines and improved standards of living and they weren’t important any more. (This seems amazing in the era of the coronavirus, and the return of measles, but AIDS arrived a generation after the polio pandemic of the 1950s and a generation seems to be enough time for a pandemic to be forgotten.) As a result, many epidemiologists had turned to chronic diseases and been very successful in, for example, the studies of lung cancer and smoking and of risk factors for heart disease. Because of these and other successes, chronic disease epidemiology had taken over in the academy and I myself had become a cancer epidemiologist. I never took a course in infectious disease epidemiology when I was at Berkeley, and I wasn’t alone; practically nobody specialized in infectious diseases. As a result, in 1982, at the Assistant Professor level, there were no infectious disease epidemiologists in the three academic epidemiology departments of the Bay Area. All there was when AIDS arrived was me, the cancer epidemiologist who happened to live in the Castro. I was ignorant but I was also arrogant. I thought I could learn whatever I needed to know.

I did know how to do case-control studies, so that was most of what I proposed. After the three haemophiliacs had been reported by Foege at the end of June, most researchers already believed the cause of AIDS was an infectious agent, probably a virus transmitted sexually and in blood, something like hepatitis B. Sexual transmission would show up in a case-control study as risk associated with numbers of sexual partners, or with specific sexual practices, or perhaps with sex in specific locations, like bathhouses. But there was a popular and highly political alternative still circulating in the gay community, the “immune overload” theory. This theory proposed that the immune disfunction was the result of the multiple infections which had been plaguing gay men even before AIDS, among them hepatitis A and B, amoebiasis, syphilis and gonorrhea. If “immune overload” was the cause, gay men with AIDS were not infected with any mystery virus and not a threat to anybody but themselves. This idea was politically popular in the parts of the lesbian and gay community that were fearful of an AIDS backlash.

Thirdly, some researchers at NIH and elsewhere were pushing the idea that poppers -- amyl and butyl nitrites used as sexual stimulants -- were associated with KS, as a small, early study by Michael Marmor had reported from New York[6]. Fourthly it was suggested that widespread drug use in the gay community (particularly methamphetamine use, which was rampant) was depressing gay men’s immune systems; there was evidence that some drugs could affect T-cell counts. Stuart Anderson, who was following all this closely, said even marijuana had been shown to lower T-cell counts. (What, I thought, marijuana?) And fifthly there was infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV), very common in gay men, sexually transmitted and a potential cancer virus.

Dennis and I assembled these ideas into a questionnaire and wrote a draft version for the proposal. We started thinking about getting access to men with AIDS to test the questionnaire. I recruited a bunch of gay volunteers, mostly men but some lesbians, to help develop the questionnaire and also to give us a way of getting connections into different parts of lesbian and gay society. These volunteers came with a wonderful collection of assorted backgrounds. They were smart and often charming people who served as buffers between us and gay politics and who did a lot of work for nothing. Some ended up on staff, among them Wally Krampf, a doctor and former pot grower who lived a couple of blocks away from me in Noe Valley with his partner Buzz, a skilled indoor cultivator. Wally, our in-house doctor, would be a tower of strength over the next few years, acting as one pillar holding up the roof of our operation (Dennis was the other pillar).

Wally and Buzz had abandoned country life up north of San Francisco in super-rural Covelo.

“They didn’t like my lifestyle in Covelo,” Wally explained.

I raised my eyebrows.

“Gay Jewish doper.”

Since Covelo was even then a terrifying bastion of rural Christian fundamentalism, I wasn’t surprised. I was surprised they had let him in in the first place

8

Enter now Louise Swig, another vitally important person in my life.

In the case-control study we had said we would compare the cases with two sets of controls, a set from the STD clinic (as in the CDC study), and a second set called “randomly selected neighborhood controls.” [7]. A randomly selected neighborhood control for an AIDS case would be a gay man in the case’s neighborhood, matched for age and chosen through a random-walk algorithm starting at the case’s house. (“One block left, two blocks right, two houses left…” etc). The random walk ended with a knock on a door. The interviewer would then ask the (male) person so located to identify himself as gay or not. If he was gay and he consented to study, we would have a randomly selected gay man as a control. If not, the interviewer would start again. This was expensive, but these controls are unbiased because of the random selection.

“You can’t do that,” various critics told us. “You can’t just knock on somebody’s door and ask him if he’s gay. He won’t tell you.” But, given what I had seen so far of the desire of gay men to understand the thing, I was pretty sure he would tell us.

We were already using neighborhood controls in the brain tumor study so Dennis had hired an expert. This was Louise Swig, a stumpy, pigtailed eccentric from the real-estate owning Swig family, owners of the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. Louise looked like an oversized little girl who had gotten big but not actually grown up. “I’m the black sheep of the Swig family,” she told us proudly. Louise was wired in gay political circles through friendships with the leaders of the Alice B Toklas Lesbian/Gay Democratic Club, a large grass-roots political operation rumored to be the biggest Democratic club in California. “Alice” (for short) was prominent in gayworld and a huge player in San Francisco politics.

Louise desperately wanted to work on AIDS. She would never say if she was actually lesbian or not (Alice had straight members) but she taught me about gay politics, which would turn out to be how I survived. Louise worked the Alices while Michael Gorman worked the Harvey Milk Democratic Club, the second biggest gay political organization and the lineal descendant of Harvey’s original political machine. (Michael also worked the gay Catholics, the Gay Sons of Harvard, the Tavern Guild and anybody else he was interested in. Michael had the anthropologist’s gift of insatiable curiosity.)

Louise, via her political connections, was, as will be seen, largely responsible for the fact that I -- that we, because, with the volunteers and with Michael and Louise and with the questionnaire design process it wasn’t just Dennis and me any more, we were now becoming a we – that we became who we became: that, in spite of my pig-ignorance about infectious diseases, we finally became actual AIDS researchers.

I carefully avoided “Patient Zero,” the research territory that was inflaming Darrow. It was CDC turf, and anyway I didn’t think it was that important. It was clear we weren’t in a Typhoid Mary situation, where one person was responsible for repeated outbreaks. We already knew there were multiple sexual connections between New York , LA and San Francisco.

We put the proposal together with scissors and scotch tape, making it probably the last grant proposal of the pre-personal-computer era.

I went down to General to give my draft proposal to Paul Volberding and there they were, Paul and Donald, tucked tightly behind a desk in Paul’s tiny office. They were sitting side by side, which suddenly reminded me of Laurel and Hardy in some movie sitting up in bed. Both of them were laughing hysterically. A ten-foot long strip of paper had spiraled out of an adding machine that n Donald was pecking on, had fallen over the edge of the desk and was pooling on the floor in front of them.

It was the budget. They had added up everybody’s individual budgets and they were laughing hysterically because the bottom line was four point two million dollars. Nobody could imagine the National Cancer Institute giving us four point two million dollars. .

***

While a cautious person might wait until the money came in, anybody in the soft money business knows you can’t wait around to start your study. In this fall of 1982 the National Cancer Institute was still working on its normal timetable because its anxiety level about AIDS had not yet been elevated. (Perhaps because the gay men and women at the National Institutes of Health, in suburban Bethesda, were still in the closet. NIH was probably even more closeted than UCSF.) The Cancer Institute proposed to run the grant review process with its usual heavy-footed deliberateness. They would site visit us in the coming spring, and with luck the money would appear in the summer or fall of 1983.

For an investigator, this incredibly deliberate process means that (a) your study has gone dead by the time you get the money, because you have lost interest, or (b) your study is irrelevant because other people have beaten you to it. It also shows the NCI had an insensitivity to infectious diseases that was worse than my own. You can’t just wait around in an outbreak. I decided to jump right in, design the questionnaire, and start interviewing men who were getting diagnosed with AIDS. This meant bootlegging the money from brain tumors (so be it) and plunging into gay sexuality. I had noted Darrow’s stiffness as he did his interviews; now I was about to find out why he was, as it were, stiff.

Stuart, the Vietnam veteran and fistfucker who was the original public health activist on AIDS was my principal informant. He helped us put the sex questionnaire together (“there is a man in San Leandro who has a horse. This horse is mainly used for sex by gay men…..”) and recruited a small group of key informants for the more specialized activities – Stuart himself for fistfucking, his friend Richard Pierce, a PhD and expert on parasites, for water sports (i.e. getting urinated on), and a UCSF administrator in my own department for S&M.

The administrator was a bottom, he told us. “Only mild S&M,” he said, mildly.

“Well I should hope so,” said Stuart. “Drawing blood, that doesn’t sound like mild S&M to me.”

“What do you mean, mild S&M?” Michael Gorman said.

“Oh you know, ropes, tying up with harnesses.”

The administrator turned out to be into disappointingly light S&M, mainly tit clamps and cock-and-ball weights. He said the Fifteen Club was for real S&M.

And what were the Fifteen Club into? He wasn’t willing to go into that. But there was a magazine called Dungeon Master that he wanted me to look at -- any time, at his place.

We exchange ughs over catheterization, mutual pissing, scat, fistfucking. We don’t see how fistfucking is erotic. He says they don’t come, either…

We are having this conversation in Trifles…and in walks Paul Dague!

9

While we were assembling the questionnaire I got further into AIDS paranoia. In October I had begun to keep the “symptom diary,” the alternative diary for things that I was afraid of, splitting it off from my plain diary. And my plain diary also featured the emergence of Alterman, my fictional character.

By the fall of 1982 Alterman was sitting out on my back deck up above the Castro “looking for Cossacks coming up Castro Street through his son’s telescope.” By mid-October he was imagining himself trapped in a gay ghetto, sending out messages on his word processor that were somehow networked across the ghetto walls.

“Help, help,” Alterman wrote, “we’re surrounded. Send guns for god’s sake. And medicine. Anybody…anybody.”

Alterman had made a transition from holocaust paranoia to AIDS paranoia. This arose from my own alarm at the possibility of a quarantined gay ghetto around Castro Street. I was beginning to be afraid that I was marking out the potential boundaries of such a ghetto. Every week we would collect the reporting data from Selma and I would mark it on my maps, making lines around the main gay neighborhoods in the Castro and south of Market, giving rise eventually to the idea that I was marking out the walls around what would be a quarantined gay ghetto. I agonized about it in my diary:

October 18 1982

Why is it a ghetto? It’s quarantined. Nobody leaves the Castro. This block would be in quarantine for sure. So would half of Market Street down to City Hall, all the way to City Hall. My office would be quarantined. Everything from Franklin St. west to the crest of Twin Peaks, down along 24th St.

This is Alterman’s fantasy of the Fall of the Castro. And for the record I am broken out in what I guess is herpes zoster including a worrying necklace of spots that looks just like somebody’s Kaposi’s lesion. One of them is big and scabbed. I am pretty sure it’s herpes.

The truth is I know how frightened I want to get so I get just that. An imprecise science though. Sometimes you get really frightened by mistake. Sometimes you cheat and don’t really get frightened at all.

This last thought was about the marijuana test for rank ordering the things I was afraid of. I had used the test when I was working in the basement of the Holocaust library to rank order my Jewish paranoia, etc, and now I was using it to rank order my fear of AIDS.

Now my diaries began to fuse and interconnect. I wrote a more-or-less daily diary in my normal life, with an occasional foray into my professional persona. Alterman, the paranoid interviewer in the imaginary Sex and Death study, came lurching out of my subconscious into the diary on his own schedule. (Alterman, of course, carried my own fear. This would be his main purpose over the next two years.) And beginning in October 1982 I wrote the symptom diary “for things I was afraid of.”

10

Meanwhile, Dennis and I had to find some patients to interview to test our questionnaire. Brent Borrowman would be the first.

The chest guy up on Parnassus that Volberding had recommended ran through the AIDS patients in the hospital when I came up. “Clowes, he has CMV ulcerative colitis. Mollo, he’s getting out to the length of time when he’s going to die. Oh, Borrowman, I bronched him on Thursday and Friday and now he has tons of cryptococcus….” He was pessimistic about their chances: “they’re all dead,” he said, waving an arm in the direction of the wards. “All dead men.”

Borrowman wasn’t a PCP case, he had a case of cryptococcal infection. I stalled for a week, taking care of my own anxieties, and finally made my way up to the eleventh floor of the hospital on Parnassus to interview him. My diaries recorded the impact. Alterman was brutal:

November 13 1982

What I actually saw today, Alterman thought, was a dying fag. He had seen Brent Borrowman, huddled, cramped, into a hospital bed on the eleventh floor. Borrowman’s legs were crisped up toward him and looked wasted under the covers. Borrowman’s hand was shaking as if he had palsy. He stared at Alterman from terrified and stunned eyes.

“I’m Arlen Alterman, I’m an interviewer from the University Health Study,” Alterman said fatuously. Borrowman looked at him as if he was a ghost.

This man is terrified, Alterman thought. This man sees death approaching and I am it. The epidemiologist is the bringer of death, he wants to get there first.

Does Borrowman know that? Does he wonder why I’m a week late? I was waiting for my spots to clear up, Brent.

And in the Symptom Diary, I spiraled off into anger and self doubt:

November 13 1982

He lived in San Francisco since 1976, seventy lovers a year. In April 1980 got into fisting for the first time. “Used crystal every time,” he said definitely. He said he liked to hang around toilets etc. This man is shivering, dying, what can I say? I don’t know how well I did. I did the interview. Often he lost track, he got tired and non-functional …

The interviews are ghastly. See, here I am writing it down. This is the only justification for this, Andrew.

What about Science?

Science my ass, what science is this going to produce?

Should we stop it then?

No, it draws attention to the problem. It provides information which may terrify others, one job of epidemiology…and who knows, somebody may figure something out.

Meanwhile Selma, anxious about being outflanked on the NCI front, was trying to do her own case-control study, competing with us and the study Darrow was doing for the CDC. This was muddying the waters. The three of us were now competing for the fifty or so surviving men with AIDS in San Francisco.

November 15 1982

Selma crazedly scheduling interviews. She came today, passive aggressive as always. ‘Yes, you should have seen Andrew hitting Selma over the head with a two-by-four,’ Michael says. Michael has declined to interview Mr Washington, the black bartender who has syphilis and KS lesions (“show us a nice one,” Conant said) because his own last anonymous lover had been black. He was pretty sure it wasn’t Washington but…. So Dennis gets him. (He’s dying, in the ICU at Children’s.)

November 15 1982.

Hello darkness my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again. I just remembered a corpse dream this morning, my old friend the corpse dream. The corpse was heaving itself up from under something, maybe the rug. It was a Tales-From-the-Crypt type corpse, from the EC comics of my youth, a rotting-corpse type corpse.

The kids want to see Creepshow but I refuse to go.

I said to Dennis today that the interview is like a secularized confession, we should allow the interviewers to give absolution. That’s why people are willing to be interviewed, they know they can confess their sexual sins. Only the living believe in diet and stress.

I was moody, irritated, depressed all weekend, angry with the kids. I put this down to Borrowman.

This morning Dennis and I discussed Borrowman. It’s dry, depressing. What I remember is Borrowman’s giving me any answer at all when he got tired. Then pointedly giving me his roommate’s name at the end, the only name he gave…

***

One thing I learned in this business is that people don’t see death. They quite literally don’t see it. They quickly wheel the body away and disappear it to the basement. Or is this my fantasy? The objective, perhaps, is to not see any corpses. Death is what we don’t see or don’t want to see.

[1] Later the T4 and T8 markers on lymphocytes were renamed CD4 and CD8.

[2] In September 1982 the “Acquired Immuno-deficiency Syndrome,” was defined by the CDC as: “A disease at least moderately predictive of a defect in cell-mediated immunity, occurring in a person with no known cause for diminished resistance to that disease.” The individual conditions making up the syndrome were listed in five categories:

A. Protozoal and helminthic infections

1. Cryptosporidiosis, intestinal, causing diarrhea for over one month. 2. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. 3. Strongyloidosis, causi;ng pneumonia, central nervous system (CNS) infection, or disseminated infection. 4. Toxoplasmosis, causing pneumonia or CNS infection.

B. Fungal infections

1. Candidiasis, causing esophagitis. 2. Cryptococcosis, causing pulmonary, CNS, or disseminated infection.

C. Bacterial infections

1. “Atypical” mycobacteriosis (species other than tuberculosis or lepra), causing disseminated infection.

D. Viral infections

1. Cytomegalovirus, causing pulmonary, gastrointestinal tract, or CNS infection. 2. Herpes simplex virus, causing chronic mucocutaneous infection with ulcers persisting more than 1 month or pulmonary, gastrointestinal tract, or disseminated infection.3. Progressive multifocal l leukoencephalopathy (presumed to be caused by papovavirus).

E. Cancer

1. Kaposi’s sarcoma in persons less than 60 years of age. 2. Lymphoma, limited to the brain.

[3] Not any more. The field is now occupied by the new Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital building.

[4] From Foreign Objects in the Rectum: “Bottles however may form suction when the mouth is upwards. One way to combat this is to pass Foley catheters past the object to allow the passage of air and relieve the suction. One may pull down on the catheters after inflation and pull the object down with them; if nothing else, get the catheters back.” Wibbelsma et al, Western Journal of Medicine, March 1979

[5] An example: if eighty percent of people with lung cancer in your lung cancer study are smokers, then the odds for lung cancer in smokers are p/1-p = .8/.2 = 4. If 20 percent of the controls who don’t have cancer are smokers, then the odds for lung cancer in non-smokers are .20/.80 = .25. The odds ratio is then 4/ .25 = 16.

[6] M.Marmor et al. "Risk Factors for Kaposi's Sarcoma in Homosexual Men." The Lancet 1982 Vol 319 1083-87

[7] Note to young epidemiologists: It’s a bad idea to use two sets of controls. If there’s a difference between the two sets of results you get with the two sets of controls you have to do a lot of handwaving to explain it away.

Engrossing revelations about the early impact of AIDS. Darkly revealing. Important and compelling.