This ninth chapter of my memoir of working as an epidemiologist at UCSF in the early days of the AIDS epidemic is about my collaborator Conrad Casavant, one of the gay faculty members in that still-closeted institution.

Dan Stites, Marcus Conant, Jay Levy, Art Amman, Donald Abrams and John Ziegler were investigators in the newly-formed AIDS research group at UCSF. Paul Volberding was the overall principal investigator on the proposal we had written to the National Cancer Institute. Harold Jaffe was the CDC’s lead AIDS researcher. Selma Dritz was the city epidemiologist.

Public Health Director Mervyn Silverman, seduced away by royalty, missed our NCI site visit.

1

In March three site visitors from the National Cancer Institute came to visit our proposal. Their chair was Arnold S. Monto, a flu expert from Michigan. Conrad Casavant, the immunologist who worked with Dan Stites, showed up for the site visit even though he wasn’t a principal investigator on the proposal. (There were seven of us on the proposal, two immunologists, two virologists, two clinicians and me.)

Conrad was the only gay man at UCSF that I actually fancied. He was tall, cheerful, a bit gangly, broad-shouldered and long-armed –- good-looking! I have no photograph of Conrad; I remember a big grin, a toothy grin. At the site visit he was friendly but ill at ease.

Some sixty research groups from practically every medical school in the country had responded to the NCI Request for Applications and the front runners were getting these visits to follow up in detail. We thought we were a shoo-in because gay San Francisco had been so hard hit. “They have to give one to San Francisco,” we told each other.

The site visitors showed up on the same day as Queen Elizabeth came to town. Mervyn Silverman, the Director of Public Health, was seduced away by royalty and never showed up for the visit. (I thought this was strange, given what was happening in San Francisco). Epidemiology was scheduled first on the visit, which I thought was a mistake. They’d be tired and bored by the time they got to the clinicians, I thought. And then I wondered if the site visitors would chew me up. I decided they wouldn’t. “After all,” I encouraged myself, “how many people know much more about this than I do?”

While we were waiting for the visitors we sat around in a room in the Cancer Research Institute up on Parnassus and told leper jokes. Conrad’s joke:

Q: How do you make a skeleton?

A: Put a leper in a wind tunnel.

It gave me a frisson because I knew Conrad had stuck himself with a patient’s needle – with Paul Dague’s needle, in fact. Conrad had also drawn blood from all Marcua Conant’s early AIDS patients to do T-cell studies on them. “They’re all dead, all dead men,” he told me in an eerie echo of the chest guy on Parnassus. “None of them has survived three years.” Conrad had stuck himself in the last week of December, the bad week when Art Amman’s baby with transfusion-related AIDS had been reported and Art had told me that fifty percent of donated blood in San Francisco came from gay men.

(“Oh, that baby died,” somebody said while we were sitting around waiting for the site visitors to arrive.)

Nobody knew what a needlestick from a patient with AIDS actually meant but the question hovered around, worryingly. Was it like hepatitis B? For hepatitis B, according to the CDC, in the pre-vaccine era the risk of infection from a single needlestick or cut exposure was between 6 and 30%, depending on the Hepatitis B e antigen status of the source case. (A positive e antigen test meant the virus was actively replicating.)

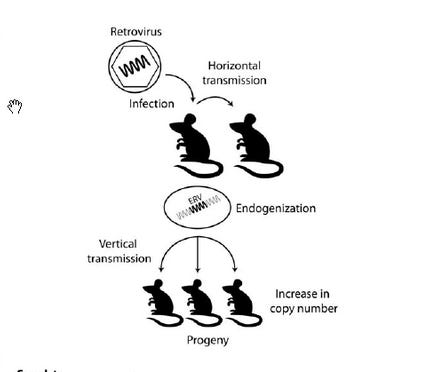

Eventually the visitors showed up and we pitched our projects. Conrad, not a principal investigator, only got to speak from the sidelines. John Ziegler gave a general introduction which was boring, but then he came out with a novel proposal to treat the patients with cisretinoic acid which turned out to be very popular with the site visitors. Art Amman did the major immunology speech for our group, sounding pretty good, if unspecific. Jay Levy showed his mouse slide -- a cartoon picture of a mouse with dozens of funny little retroviral beings on it with various virus names. “The virologists were OK,” I wrote in my diary, “and very supportive.” I sound as if I was a little surprised at this. Marc Conant gave a big pitch for his nurse, Helen Shietinger, which I stuffily thought was inappropriate because that wasn’t what research grants were for.

“Anyway,” I wrote in my diary, “it held together.”

But I also wrote that I knew that I had made three mistakes at the site visit. I didn’t say yes when somebody asked if we were going to collect blood for laboratory studies, I didn’t have a snappy comeback when somebody asked if my case-control study was “just a CDC-type study,” nothing new, and I didn’t say yes when they said “Do you intend to follow the patients up?”

“What am I supposed to do,” I wrote querulously in my diary, “lie? We’re only asking for $120 grand, that’s one study!”

I should have lied. Also, I should have been quite a bit smarter. In fact I blew it at the site visit, for which I would pay, shortly.

We had finished our meeting with the site visitors and now we were waiting upstairs in the Cancer Research Institute lounge. We had displaced the cancer patients on their drips and we were sitting around in their armchairs waiting for the site visitors to come back to us with follow-up questions.

When the phone rang for me I put my jacket on as if the visitors could see me, producing ridicule from Volberding. The only thing the site visitors wanted to ask about was the rent money we had put in our proposal. This caused me to stutter guiltily on the phone, I don’t know why. We would need rent money anywhere off campus, why would I feel guilty about it? UCSF would never let me into the main campus on Parnassus because research space there is -- well, Nobel Prize winners want that space. So I was going to need rent, for Gough Street or for some off-campus site like it, and they made me feel guilty for asking for it!

While we were waiting in the Cancer Research Institute lounge I thought about collaboration. All that year I struggled with Dan Stites, Conrad’s boss and the Chief of Clinical Immunology at UCSF. Eventually Conrad would mediate between me and Dan and eventually make it come out right.

Importantly for me, Conrad had a brass plaque on his desk that said “Second Class Doctor.” This meant he was a PhD, like me. I appreciated him putting a plaque out front that said he wasn’t a physician, and I understood why he did it. It saves complications when an actual physician suddenly realizes you’re not one of them and then feels guilty about showing it and then feels pissed off at you for having made him feel guilty. I should have had a plaque like that myself, but I was more aggrieved by the situation than Conrad. I was putting my aggravation into a teeth--gritted determination to succeed, even though I was a second class doctor in an adjunct line, which was about as far down the UC hierarchy as you could get. And I had no publications! This was shameful: you were judged by your publications.

So, publications, what are they? The medical journals are arranged in a hierarchy, and special attention is paid to publication in the top journals, The New England Journal of Medicine, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and the English Lancet, and also to the top science journals Science and the English Nature. These are the highest tier, and if you get published by them the press covers it and everybody notices. Ziegler’s lymphoma paper had been in the Lancet, when he was making his attempt to be PI.

Next down are the leading specialty journals, the Annals of internal Medicine, for example, where Jaffe and the CDC would eventually publish their case-control study, or Virology, or Pediatrics, or Chest. Below that nowadays are the subjournals the principal journals have spun off, like Nature Cardiovascular Research or JAMA Oncology. And also down there are murky lower tiers descending to European journals that even the library doesn’t carry. Somewhere down in the second or third tier was The American Journal of Epidemiology, where I would eventually put my case-control study. Down there too, probably even further down, was The Journal of Occupational Health, which would eventually publish my hospital workers’ study. Both were heartbreaking experiences; my beloved studies were shuffled down the hierarchy into third-tier journals that nobody read. (But of course even the third tier counts for your promotion.)

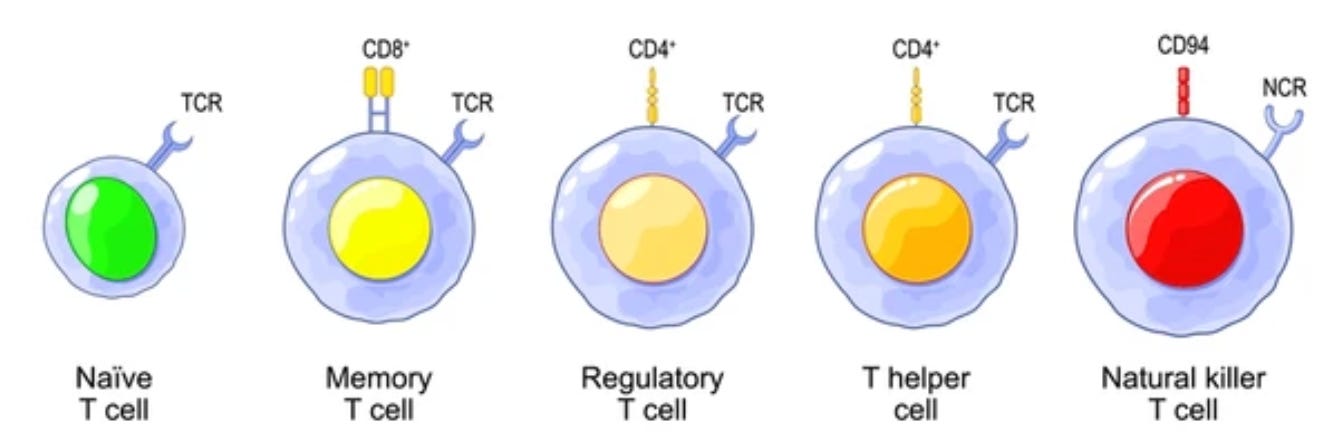

So who was Conrad in 1983? On the web there appears Conrad Casavant’s scientific publications while affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, and other places. It lists 18 publications going back to 1979. They are mostly about the FACS, the brand new cell-sorting technology that Dan and Conrad were using to count T-cell subsets. This technology had miraculously been invented just at the time AIDS, the disease that actually targets the T4 subset of lymphocytes, appeared among us. Now we were learning to think of the patients in terms of their T-cell counts, first the ratio of T8 to T4 cells, (later called CD4 and CD8 cells) and then , when we got a better idea of the pathology of the disease, the absolute number of T4 cells. It was Dan and Conrad who did the T-cell counts.

I saw that Conrad had been on Ziegler’s lymphoma paper in the Lancet (as the sixth of ten authors on a paper presenting four lymphomas!). That paper had come out in October 1982 when we were voting for principal investigator. How did Conrad vote? I don’t know – maybe for Ziegler? Actually I can’t picture Conrad, with his gentle, warm and somewhat seductive personality, paired with Ziegler’s NCI chilliness and ambition.

Conrad's last published paper was in 1988 and I was on it too: “Interrelations of lymphocyte subset values, human immunodeficiency virus and antibodies, and HIV antigen levels of homosexual males in San Francisco,” by John Crowka, published in Diagnostic and Clinical Immunology. The homosexual males were from my cohort study, which, like all successful cohort studies, had by then become a powerful research machine producing many collaborations with all kinds of scientists.

This last paper, the one that we were both on, was published posthumously. Conrad died of AIDS in 1987.

2

After the site visit we went upstairs to the CRI patient lounge to wait for possible followup questions from the visitors. Conrad had seemed uncomfortable during the site visit, although he had cracked his leper joke while we were waiting for the thing to begin. I wondered how Conrad could make leper jokes, when he had stuck himself with Paul Dague’s needle. It was denial at work, of course. Leper jokes were apotropaic: they warded away evil.

Conrad was the only gay person sitting in the waiting group in the CRI patient lounge. Marc Conant had disappeared and Donald was, as usual, detached from the rest of us -- running around, absorbed in making phone calls, writing up his notes. There was a general release of tension now that the site visit was more or less over and people began joking around, telling grant stories. Somebody observed that four small grants had already been funded by the NCI.

“Houston’s got one, that’s the pigs,” said John Mills, the head of ID at San Francisco General.

“Pigs?” somebody said.

“Yes, pigs are naturally homosexual, it seems. Also they lap up semen too, so you get it both ways.”

“Giraffes are naturally homosexual too” said Ziegler.

There was a silence while everybody tried to get their minds round this. Conrad made some awkward comment and I thought “he’s alone here because he’s gay.”

And then somebody started talking about Friedman-Kien, the NYU dermatologist, who had apparently asked for four million dollars in his response to the RFA.

“One for him,” somebody said.

“Friedman-Queen,” somebody else said, snickering.

I watched Conrad squirm. I thought it was a squirm for “Friedman-Queen” but maybe it was for the pigs too. Maybe it was for the general consensus in the patient lounge that being homosexual was somehow comic, a joking matter. Or perhaps all of this was because homosexuality was a tense enough matter in our immediate situation -- in the middle of a homosexual epidemic that we were all desperately trying to come to grips with, hoping to prise enough money out of the NCI to keep going -- for us to need the anxiety to be defused by humor. Nobody said anything more but it felt to me like the lid had come off for a moment.

***

I can’t find Conrad’s photograph on the internet. I find Paul Volberding, Connie Wofsy (the infectious disease specialist in the AIDS clinic in Ward 86), Donald Abrams (a nice portrait, with a thoughtful finger up against his cheek) me, Amman, Conant, Merle Sande (Chief of Medicine at SF General), Selma --everybody but Conrad. I try again using Conrad’s boss Dan Stites’ name, thinking there must be some kind of two-shot of the two immunologists in the UC files, but here comes Molly Cooke (Paul Volberding’s wife), me again, Merle Sande again, Julie Gerberding (Merle Sande’s girlfriend), but no Conrad. Conrad died in 1987, which perhaps was too early for his photo to make it onto the internet.

Anyway, I liked Conrad a lot, and appreciated his support – he actually seemed to have a positive attitude towards us, the epidemiologists, while Dan didn’t. After we got the final NCI review, which torpedoed me, Dan waved his hand at my efforts to stay funded--meaning it was all sort of diffuse -- and said “This approach has been turned down by the NCI and the State” as if to say “Why don’t you just go away?”

But John Greenspan, a late addition to the research group who ran the serum and tissue repository for us up on Parnassus, told me confidentially that these people were really not scientists, they were just interested in getting money. “They’re in a very high-profit department, you see,” he said.

For a moment I wished I was in a high-profit department too.

Eventually Conrad said not to think Dan wasn’t committed to this and definitely in no way was he trying to kick you off and he and Dan were in this together. He must have talked Dan into it. I looked at the brass plate saying Second Class Doctor and thought “OK Conrad, I get the message.”

Now I think “OK Conrad, thanks.”

fine story telling...

excellent chapter, mate, all the many emotional threads kept in play, refreshing frankness from you as usual, and especially engaging, and touching, to learn about Conrad. Have shared this with a couple brainy medical friends